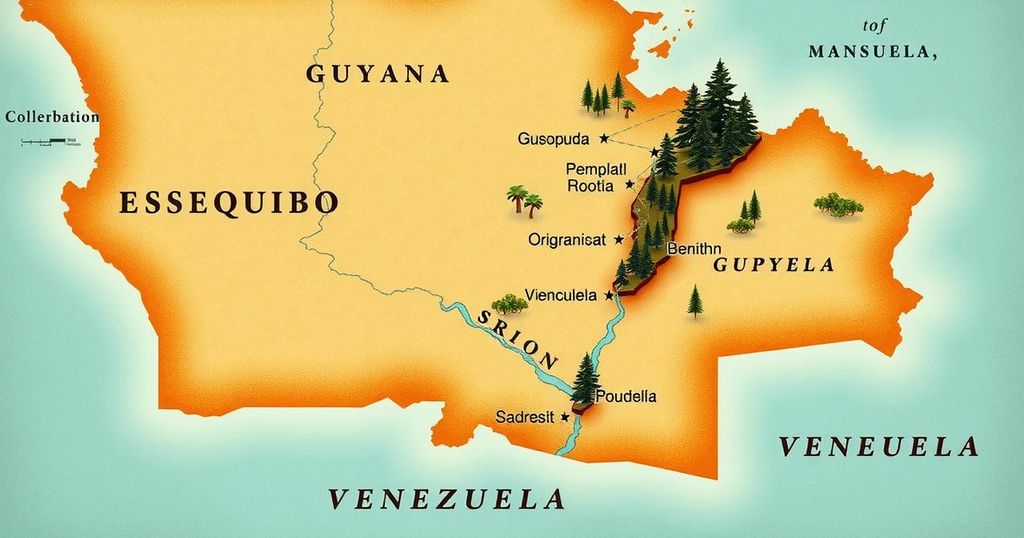

Venezuela’s government plans elections in Guyana’s Essequibo region, challenging established international norms and the authority of the ICJ, raising tensions and concerns about legal accountability. With Essequibo’s rich resources in play and cross-border provocations reported, the situation risks escalating into conflict, highlighting the need for diplomatic solutions and adherence to international law.

On May 25, just a day before Guyana marks its 59th independence anniversary, Venezuela’s government under Nicolás Maduro announced plans to hold elections in the Essequibo region. This territory, almost two-thirds of Guyana, is fully within its recognized borders. This action, rather than being an expression of democratic principles, almost seems to be a blatant challenge to international legal norms and raises serious concerns about respecting the authority of the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Essequibo has been regarded as part of Guyana since an 1899 arbitral award settled the border issue. That decision, also binding, was made by a tribunal featuring Chief Justices from Russia, Britain, and the United States, with Venezuela’s own nominee in the room. At the time, Venezuela accepted the ruling, even referring to it as a diplomatic success as it expanded its territory, notably gaining access to the crucial Orinoco River.

For over sixty years, both nations recognized this boundary. However, things took a turn in 1962 when Venezuela challenged this award at the United Nations. In 1966, right before Guyana’s independence, both countries signed the Geneva Agreement, an effort to resolve the issue peacefully, which included empowering the UN Secretary-General to find a settlement if other methods failed.

In 2018, after many stalled discussions, the Secretary-General referred the long-standing dispute to the ICJ, leveraging the powers granted by the Geneva Agreement. Guyana sought a ruling that confirmed the legitimacy of the 1899 award. At first, Venezuela contested the court’s authority and refrained from participating. Even after submitting some documents, it still refuses to comply with the jurisdiction of the Court, disregarding interim measures, including a May 1, 2025, order that explicitly warned against conducting elections in the disputed territory.

Despite this order from the ICJ, Venezuela’s National Electoral Council has expressed intentions to elect officials in Essequibo, announcing elections for eight deputies and a governor. Surprisingly, no clear details about voter registration or polling processes have been revealed, which is expected given that Venezuela has no recognized authority in Essequibo.

In response to this provocation, the Maduro administration leans on a 2023 domestic referendum it organized without any sort of watchdog oversight. Based on that outcome, it has claimed authority over Essequibo. Following this, the Venezuelan National Assembly passed legislation that would seemingly formalize the incorporation of Essequibo into Venezuela, stating that officials would be managed from Tumeremo in Bolívar State, far from the actual region in question.

This move raises significant moral questions—how can one hold elections over a territory it does not govern? The answer is fairly simple: it cannot, except through acts of occupation. Should Venezuela act on this, it would not only violate the ICJ’s orders but also breach the UN Charter and the Organization of American States’ principles against using force to settle territorial issues.

The drivers behind these latest actions likely stem more from geopolitical interests rather than genuine nationalism. Essequibo’s wealth in resources—ranging from oil to gold—has become increasingly vital, especially amid Venezuela’s mounting economic troubles. Legal justification seems to take a back seat in the grand scheme of things here.

Meanwhile, on-ground tensions are reportedly escalating, with reports of cross-border provocations from Venezuelan forces being noted by Guyana’s defense officials. The Guyanese government has also cautioned that participating in the May 25 elections could be seen as a criminal act. Notably, around 100,000 Venezuelans currently live in Guyana, many fleeing the hardships back home. It’s crucial these individuals aren’t pulled into a conflict that endangers their well-being.

The international community must take this matter seriously. The ICJ is the recognized forum to arbitrate this longstanding dispute, and both parties must respect its jurisdiction. Any attempts to sidestep the ICJ through unilateral actions could undermine international legal systems designed for peaceful resolutions, thus threatening regional stability.

Neighboring Caribbean countries and global partners who advocate for international law must send a strong message: borders can’t be changed based on internal laws, and no nation stands above legal accountability. Elections held in disregard for jurisdiction do not bring legitimacy—on the contrary, they stir conflict.

Guyana and Venezuela are geographically locked in place; neither can simply move away. But clearly, peaceful coexistence cannot be based on unilateral decisions or threats. Instead, it requires respect for legal frameworks, mutual recognition, and diplomacy. It is essential to await the ICJ’s ruling and build a cooperative relationship benefitting both nations.

In the end, diplomacy and the rule of law are the only genuine pathways to peace. That route must not be neglected.

In summary, Venezuela’s recent election plans for the Essequibo region illustrate a dangerous shift in its approach to a longstanding territorial dispute with Guyana. Violating international laws and court orders won’t solve the issue but could exacerbate tensions. The call for respect for the ICJ’s authority is clear; both nations need to prioritize peace and set aside unilateral actions. Dialogue, grounded in law, is vital for a true resolution.

Original Source: www.thestkittsnevisobserver.com