Shark Island, a site of colonial genocide, is being developed as a tourist campsite amid plans for green hydrogen production in Namibia. However, advancements threaten the historical and ecological significance of the area. Advocates emphasize the need for meaningful engagement and recognition of the past as Namibia balances development with its turbulent colonial history.

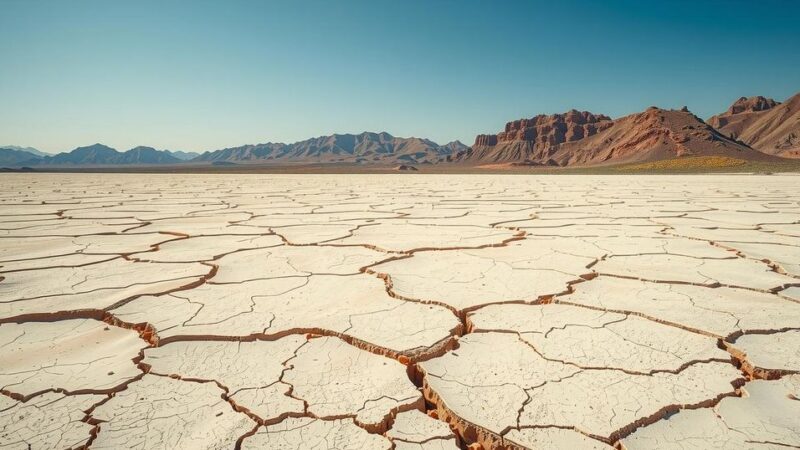

Shark Island, situated near Lüderitz, Namibia, is undergoing transformations as it becomes a tourist campsite. Yet, beneath its recreational surface lies a tumultuous history marked by colonial violence, particularly during German rule from 1884 to 1915, when it was known as Death Island and served as a concentration camp where thousands perished.

Namibia is strategically positioned to produce green hydrogen, touted as a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels, especially as the country prepares for the Global African Hydrogen Summit in September 2025. However, port expansion plans to facilitate this production threaten the historical significance and ecological integrity of Shark Island, an area steeped in painful memories for many Namibians.

The German colonial regime inflicted severe violence on the Herero and Nama populations, resulting in the death of over 100,000 individuals. Survivors were subjected to relentless forced labor in concentration camps. Although physical reminders of these camps are scarce, recent investigations have brought key burial sites into focus, underscoring the ongoing need for recognition of this violent history.

Forensic Architecture’s digital reconstructions of the concentration camps on Shark Island reveal that proposed infrastructure projects could endanger these important memorials. While green hydrogen initiatives have sparked significant investment interest, they often overlook the ocean’s historical context, which is interwoven with Namibian trauma and memory.

This trauma is compounded by historical practices where colonial authorities disposed of deceased individuals at sea. The saying “the sea will take you” reflects the deep-rooted connection between the ocean and the memory of loss in the affected communities, underscoring the need for memorialization and justice in modern development agendas.

To navigate this precarious landscape, local advocates urge the Namibian government to reconsider port expansion plans and engage in meaningful reconciliation with communities affected by genocide. The involvement of organizations like Black Court Studio highlights the necessity of acknowledging and addressing the ongoing legacies of colonialism in Namibia’s green energy narrative.

Although green hydrogen is promoted as an essential component of global energy transformation, the dynamics between Namibian coastal communities and European interests raise ethical questions about energy colonialism. Development assistance from European nations is often perceived as a means to perpetuate historical injustices rather than a genuine contribution to local empowerment and descent rights.

Creative projects that engage with the ocean’s role in the historical narrative of Shark Island aim to restore cultural and spiritual connections that have been disrupted by colonial exploitation. This work serves to emphasize the importance of viewing the seas and coasts not merely as economic resources but as integral elements of community identity and heritage. Acknowledging these connections is crucial for fostering genuine reconciliation efforts in Namibia.

Shark Island in Namibia, once a site of colonial genocide, faces new threats from development projects aimed at producing green hydrogen. Local advocates emphasize the need for recognition and justice regarding past atrocities as current infrastructure plans risk exacerbating historical grievances. Comprehensive reconciliation efforts that honor cultural and spiritual ties to the land and sea are vital in ensuring equitable development that truly benefits affected communities.

Original Source: www.independent.co.uk