Exiled Sudanese artists Rashid Diab and Yafil Mubarak discuss preserving their cultural identity amidst the civil war devastating Sudan’s art scene. The war has erased numerous artworks and forced millions into displacement, which influences artists like Yasmeen Abdullah and Ala Kheir. They strive to share Sudan’s rich narrative of resilience, asserting their cultural significance against the backdrop of conflict.

Rashid Diab, a prominent Sudanese painter and art historian, and his son, Yafil Mubarak, engage in a reflective video call from their studio in Madrid. They discuss the impact of exile on their identities as artists and the fate of their homeland’s art scene. Diab contextualizes their conversation with a critical question: “How do we preserve the real Sudanese?” It sparks an exploration of national pride and the essence of Sudanese identity amidst tragedy.

Since the outbreak of civil war in April 2023, Sudan’s art scene has suffered a devastating decline. Just as galleries in Khartoum were beginning to flourish, the war led to their destruction and abandonment, erasing years of cultural development. Notably, the Downtown Gallery was a significant venue showcasing over 500 works, including pieces from both established and emerging Sudanese artists. Founder Rahiem Shadad lamented, “I think in the thousands. I believe we’ve lost thousands of artworks” due to the ongoing conflict.

Forced from their homes, more than 12.5 million Sudanese have now become displaced, including notable artists such as Yasmeen Abdullah, who finds inspiration in her past while residing in Muscat, Oman. She creatively expresses her experiences through evocative artwork, reflecting on memories and hope. Abdullah states, “But art never left me, even in my darkest moments. In the midst of the darkness, there was light.”

Artist Ala Kheir, now a nomadic photographer, seeks to document the real Sudan beyond its war-torn narrative. His project, The Other Vision, has pivoted to focus on the country’s destruction and the resilience of its people, revealing shares of diversity often overlooked. Kheir highlights the necessity of creating a human narrative amidst conflict, saying, “If I don’t do it, no one else will.”

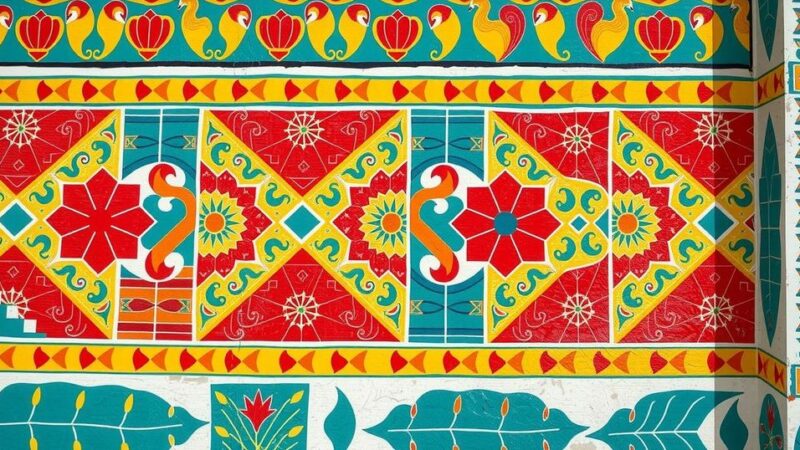

Diab questions the essence of creating “African art” while in exile, emphasizing his connection to Sudan through memory and cultural heritage. His paintings capture life’s rhythms and encapsulate the spirit of Khartoum, now lost to him. He mourns the destruction of his cultural space and dreams, aware that his spirit remains tethered to Sudan despite physical separation.

Collage artist Yasmin Elnour, residing in London, explores identity through her art, influenced by her own family’s exodus from Nubia due to the Aswan Dam’s creation. Elnour probes deep philosophical questions of existence and identity in her work, asking, “Does identity need a physical place to exist?”

In this moment of diaspora, Sudanese artists continue to create from afar, asserting their roles as ambassadors of their culture. Mubarak emphasizes the importance of their artistic contributions as a narrative of resilience, stating, “We can show the world that Sudan is more than endless civil war and bloodshed. We are thinkers, creators, we have philosophy, we have art.”

The ongoing civil war in Sudan has had a catastrophic impact on the country’s burgeoning art scene, leading to displacement and loss of countless artworks. Exiled artists like Rashid Diab, Yasmeen Abdullah, and Ala Kheir are now struggling to preserve their cultural legacy while grappling with their identities. Despite the turmoil, they stand resilient, using their art to portray Sudan’s complexity and history, showcasing a narrative of hope amidst despair.

Original Source: www.artnews.com