A study reveals that recovery from mammalian extinctions in Madagascar could take up to three million years, and if threatened species vanish, recovery may exceed 20 million years. This highlights Madagascar’s critical biodiversity status and the urgent need for effective conservation efforts to avert imminent extinction threats.

A recent study conducted by international scientists, including Dr. Liliana M. Dávalos from Stony Brook University, indicates that recovering species lost due to human activities in Madagascar could take up to three million years. Published in Nature Communications, the research reveals a concerning trend: if currently threatened species become extinct, recovery may exceed 20 million years, making it one of the longest recovery times globally for an island archipelago.

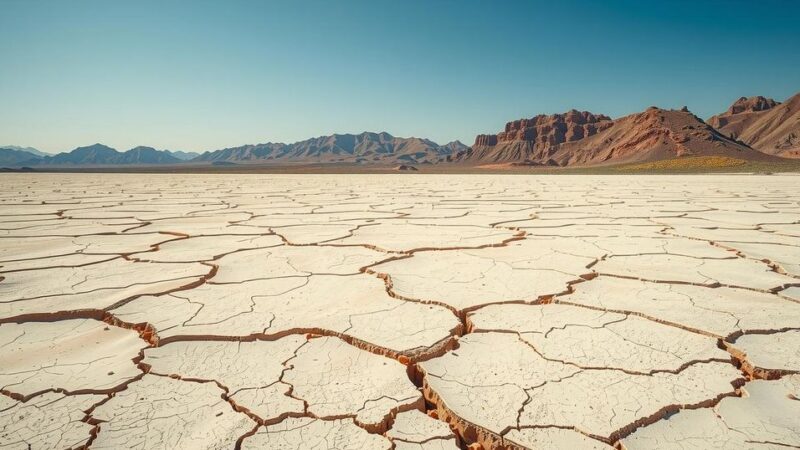

Madagascar is renowned for its exceptional biodiversity, housing approximately 90% of species that are exclusive to the island, including iconic plants and animals like lemurs and baobabs. Since human settlement began 2,500 years ago, Madagascar has witnessed numerous extinctions, among which were giant lemurs and elephant birds. However, over 200 mammal species currently remain, with over half classified as threatened, largely due to agricultural transformations of habitats.

To investigate the impact of human activity on Madagascar’s ecological state, the research team developed a comprehensive dataset outlining the evolutionary relationships of all mammal species present at the time of human colonization. They identified a total of 249 species, including 30 extinct species, highlighting that more than 120 of the remaining 219 species are currently threatened according to the IUCN Red List.

Employing a computer simulation model rooted in island biogeography theory, the team, spearheaded by Nathan Michielsen and Luis Valente from Dutch institutions, estimated it would take approximately three million years to restore mammal diversity lost due to human actions. Alarmingly, should currently threatened species face extinction, recovery could take about 23 million years, a figure that has significantly risen over the last decade due to escalating human impact.

Dr. Dávalos emphasized the urgent need for conservation, noting the role of ongoing research at the Centre ValBio and Ranomafana National Park for local communities’ livelihoods. Leading researcher Luis Valente highlighted the uniqueness of Madagascar’s biodiversity, asserting that the time to recover from extinctions is considerably longer than recovery times reported for other islands, such as New Zealand and the Caribbean.

The study underscores an imminent wave of extinctions that could cause profound evolutionary impacts on Madagascar. Encouragingly, the simulation model suggests that with sufficient conservation measures, it is possible to safeguard over 20 million years of the island’s unique evolutionary history.

The study emphasizes the critical state of Madagascar’s biodiversity, forecasting potentially catastrophic extinction timelines if urgent conservation efforts are not enacted. It underscores the invaluable uniqueness of Madagascar’s species and the surprising length of biological recovery periods compared to other regions. Furthermore, it highlights the significant potential for conservation to preserve Madagascar’s rich evolutionary past, emphasizing dedicated local research and initiatives.

Original Source: news.stonybrook.edu