In 2024, Bolivia faced devastating wildfires that burned over 10 million hectares, affecting water supplies and food security. Communities were displaced, health issues arose from smoke and water pollution, and the socio-economic fabric was strained, particularly for women and children. Long-term effects and challenges remain significant, raising concerns over future sustainability and recovery efforts.

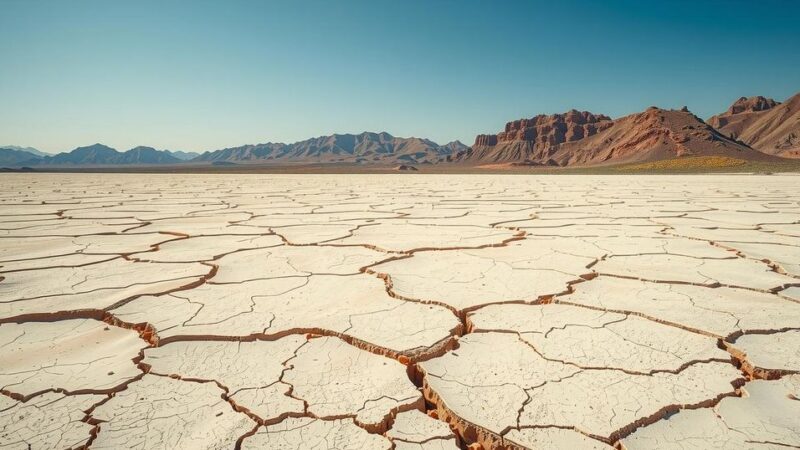

In 2024, Bolivia experienced its worst wildfires, consuming over 10 million hectares, an area larger than Portugal. The fires and preceding droughts severely depleted water sources, impacting communities like Los Ángeles, where Isabel Surubí had to leave her family home due to the dry spring.

Last year’s wildfires devastated more than 10% of Bolivia’s forests, primarily driven by slash-and-burn agriculture associated with large agroindustrial operations. Surubí’s community, located in the eastern Chiquitanía region, faced immediate displacement as fast-growing shrubs replaced the lost trees, while health impacts from the fires continued to emerge even seven months later.

Further southeast, residents in Santa Ana de Velasco are grappling with lingering effects of the fires. Local nurse Wilmar Cristian Gonzales Ortiz detailed dire conditions during the fires, with residents exposed to extreme heat and smoke while attempting to protect their homes and crops. Over 21,000 patients required treatment for fire-related health issues in the broader Santa Cruz region last year.

The water contamination following the wildfires has led to numerous gastrointestinal problems, with Gonzales Ortiz reporting a surge of patients with stomach pains, vomiting, and diarrhea. The potential for severe long-term health complications remains, as experts warn of respiratory issues manifesting years down the line, including lung cancer and chronic illnesses due to ash exposure.

Communities also confront food insecurity exacerbated by wildfires and climate change risks. Verónica Surubí Pesoa reported severe crop losses, likening the situation to “work in vain” as local farmers struggle with rising food prices and limited agricultural output. Many who once farmed are now forced to seek low-paying work on large ranches.

Although the Bolivian government declared the wildfires a national disaster and implemented a ban on agricultural burning, criticism arose from smallholders reliant on this method for cultivating crops. Educational disruptions were common as schools reduced hours in response to the hazardous conditions, further exacerbating the impact on students’ learning.

The aftermath of the fires has also seen increased burdens on women, who now tackle extensive responsibilities, including health and education roles in their families. Rosa Pachurí highlighted these changes, noting that the simultaneous migration of men for work has left women managing most household duties.

Instances of sexual violence against women and girls reportedly escalated during the crisis, although data on these assaults remains scarce due to underreporting. Isabel Surubí expressed hope of returning home but worries that without restoration of the local water supply, hunger could claim more lives than the fires themselves.

“If we aren’t killed by fire,” she reflects, “we’ll be killed by hunger.”

The aftermath of Bolivia’s catastrophic wildfires in 2024 has led to significant displacement, health crises, and food insecurity among local communities. As families like Isabel Surubí’s are forced to abandon their homes, the socio-economic impact of such environmental disasters continues to unfold, with particular vulnerabilities highlighted among women and children. The lasting effects pose serious questions about recovery and sustainability as communities strive to rebuild.

Original Source: www.theguardian.com